Information Architecture for Websites: Card Sorting and Tree Testing Explained

Updated on

Published on

A website can have strong creative and still underperform because users cannot find what they came for. That gap hits marketing first. Paid clicks bounce, organic traffic stalls, and sales teams get low intent leads because the path to the right page is unclear.

Information architecture for websites is the quiet system underneath navigation, labels, and page groupings. When it is coherent, users move with confidence. When it is not, every campaign pays a tax in wasted attention and friction.

Card sorting and tree testing are two practical methods to reduce that tax. Card sorting ex poses how people naturally group information. Tree testing validates whether a proposed navigation structure actually works in real tasks. Used together, they turn opinions about the menu into evidence.

At a Glance: Card Sorting vs Tree Testing

Card sorting and tree testing solve different parts of the same problem. You get the best outcome when you treat them as a sequence, not a choice.

- Card sorting is generative. It helps you discover how users group topics and what labels feel natural. It is especially useful early in information architecture for websites when structure is still flexible. (Nielsen Norman Group)

- Tree testing is evaluative. It tests whether users can find items in a proposed navigation tree, using text only. It is ideal once you have a draft sitemap and labels. (Nielsen Norman Group)

- Card sorting informs what the buckets could be. Tree testing confirms whether those buckets actually work.

- Both can be run quickly, remotely, and with measurable outputs. That makes them useful for teams under timeline pressure.

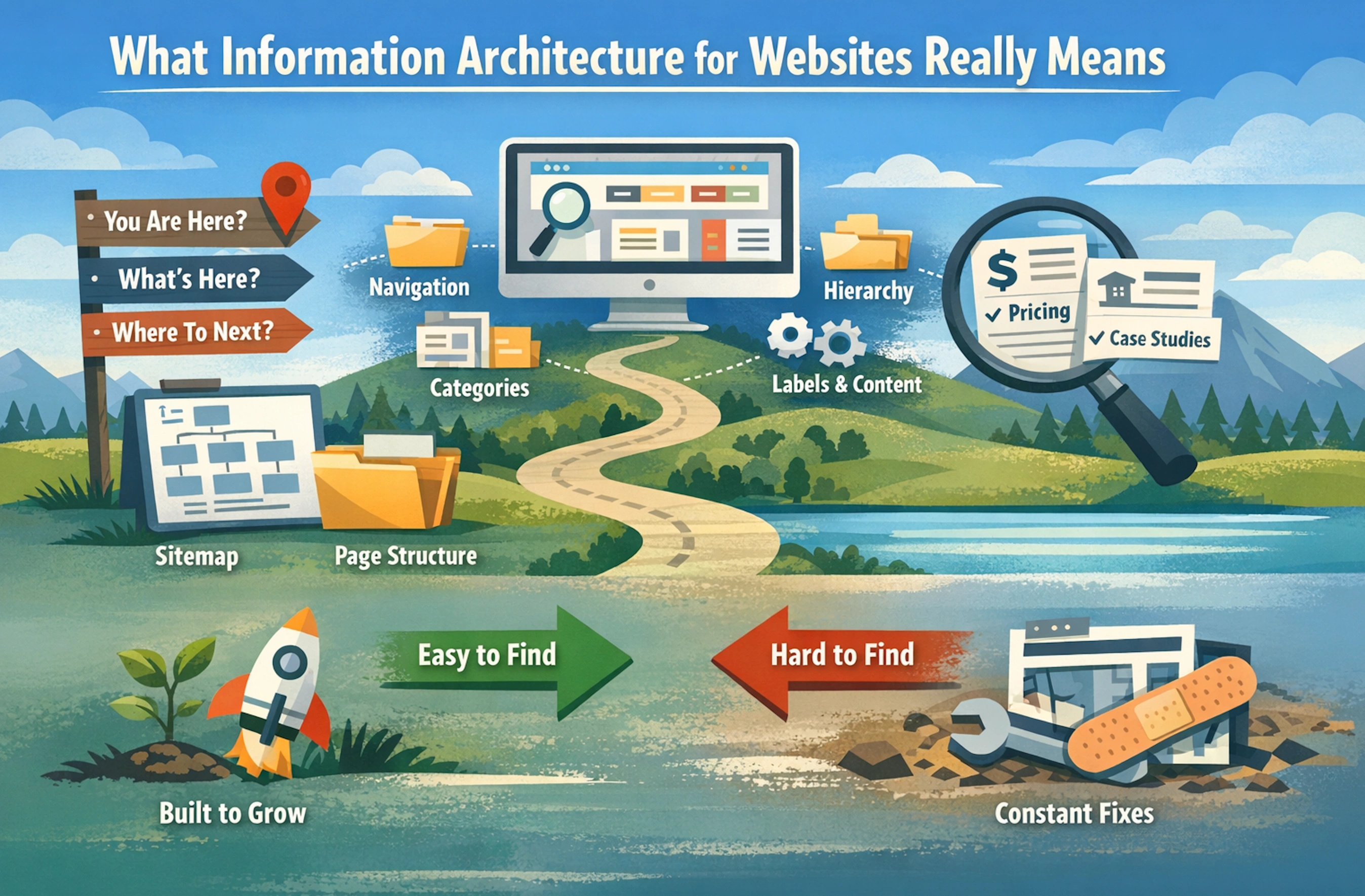

What Information Architecture for Websites Really Means

Information architecture for websites is the way content is organized so users can predict where things live. It includes the navigation model, page hierarchy, category structure, and the language used in labels. It also includes how content is chunked across pages so key information is discoverable without hunting.

A practical way to think about website information architecture is that it answers three questions for a user.

- Where am I right now?

- What else is here?

- Where should I go next?

When those questions are answered implicitly, websites feel easy. When they are not, the site feels larger than it is, even if it has only a few dozen pages.

For marketing teams, information architecture for websites matters because it controls message match. If a campaign promises pricing, the navigation and page naming should make pricing easy to find. If a campaign promises case studies, the path to proof should not be buried under Resources with ambiguous labels. This is why navigation structure and findability are not just UX problems. They are conversion problems.

If your team treats information architecture as part of web design services, you tend to build a site that carries growth over time. If you treat it as a last minute sitemap exercise, you tend to build a site that needs constant patching.

Card Sorting Explained: When It Works and What It Reveals

Card sorting is a user research method where participants organize topics into groups that make sense to them. The output is not a final sitemap. It is a set of patterns about how users expect information to be structured and labeled. (Nielsen Norman Group)

In information architecture for websites, card sorting is most useful when you have too many competing assumptions. Stakeholders often group content by internal org structure. Users rarely do. Card sorting is a fast way to see the difference.

It is also valuable when labels are vague. A team might assume Solutions is clear. Users might group those pages under Services, Use Cases, or By Industry depending on what they are trying to do. Card sorting shows where language becomes a decision point.

Open, Closed, and Hybrid Card Sorting

Open card sorting is best when you want to discover categories and labels from scratch. Participants create their own group names. That helps you understand mental models and naming conventions.

Closed card sorting is best when you already have categories and want to validate where items belong. Participants sort items into fixed buckets. That helps you test whether your current navigation structure is intuitive.

Hybrid card sorting blends both. Participants can use existing categories but can also create new ones when nothing fits. That helps you refine a draft structure without forcing users into bad buckets. (Nielsen Norman Group)

In practice, hybrid card sorting is often the most efficient for website information architecture because most teams already have a sitemap draft, even if it is rough.

Remote vs In Person Card Sorting

Remote card sorting is usually enough for information architecture for websites. It scales easily and avoids scheduling friction. It also reduces conference room dynamics where participants try to please the moderator.

In-person card sorting can be useful when you want richer qualitative insight, especially for complex content sets. It can also help when you need to watch hesitation and confusion live. The tradeoff is time and cost.

For many businesses, a remote approach paired with a short follow-up interview gives a strong signal without slowing the redesign.

Tree Testing Explained: How to Validate a Navigation Structure

Tree testing evaluates a proposed navigation tree by asking users to find specific items using only the structure and labels. There is no page design, no visuals, and no on-page content. That is the point. Tree testing isolates information architecture for websites and tests pure findability. (Nielsen Norman Group)

Tree testing is most useful after you have a draft sitemap and top-level labels. It is also useful when you suspect that a redesign looks better but still might not be easier to navigate. Because tree testing strips away design cues, it prevents a common false positive where users succeed only because a button is visually prominent.

If card sorting reveals how users group ideas, tree testing validates whether your navigation structure actually supports real tasks.

Tree Testing Tasks That Mirror Real User Intent

Tree testing tasks should reflect what users actually want to do. Not what the org chart suggests. A good task is written as a scenario with a goal.

- You want to compare plans before booking a call. Where would you go

- You need support documentation for an existing product. Where would you look

- You are evaluating whether the company serves your region. Where would you find that

These scenarios map directly to marketing journeys. They also reveal where navigation labels are too abstract to support intent.

A useful rule is to include both high-intent and low-intent tasks. High-intent tasks reflect conversion readiness. Low-intent tasks reflect early research. Information architecture for websites should support both without forcing users into the wrong funnel stage.

Metrics That Matter in Tree Testing

Tree testing produces measurable outcomes that help you prioritize changes. Nielsen Norman Group highlights tree testing analysis metrics like success and path behavior. (Nielsen Norman Group)

The metrics that tend to matter most are:

- Task success rate, whether users reached the correct destination

- Directness, whether users took an efficient path or wandered

- First click, where users start, which is often where labeling problems show up

- Common wrong paths, which reveal competing interpretations of labels

These outputs help you separate a structural problem from a wording problem, which saves time when you iterate.

A Practical Card Sorting Process You Can Run in a Week

A card sorting study does not need to become a research program. For most websites, a focused card sort can be run in a week, with clear outputs for a sitemap draft.

Start by defining what you are sorting. Card sorting works best when the card set reflects real navigation candidates. That usually means pages, content topics, product areas, or support concepts. Keep it grounded in what a user would recognize.

Next, decide which audiences matter. A site that serves multiple audiences can still run one card sorting study, but you need to recruit participants who represent the primary audience. Otherwise, you will get a blended mental model that matches no one.

Then run the sessions and analyze patterns. You are not looking for unanimous agreement. You are looking for stable clusters and repeated label choices. Those patterns become the basis for website information architecture decisions.

How to Build a Card Set Without Bias

The card list is where many teams bake in bias. If a card contains internal jargon, participants will group based on guesswork. Use plain language on cards. If you must include internal terms, add a short clarifier.

Keep cards at a consistent granularity. Do not mix high-level categories like Services with detailed items like On page SEO checklist. When the levels are mixed, participants group based on abstraction rather than meaning.

A strong approach is to start with your existing sitemap, then rewrite labels into user-facing language, then remove duplicates. The goal is not to mirror your site map. The goal is to test information architecture for websites as a user would perceive it.

How Many Participants You Actually Need

Nielsen Norman Group’s long-standing recommendation is that many card sorting studies work well with around 15 participants, with higher numbers for large or high-stakes projects. (Nielsen Norman Group)

The practical takeaway is not a magic number. It is that you want enough participants to see stable clustering patterns. If your participants are highly diverse, you may need more. If your audience is narrow, you may need fewer.

If you are running information architecture for websites research under time pressure, prioritize participant quality over pure quantity. Ten participants who match your core audience often beat thirty who do not.

A Practical Tree Testing Process You Can Run in Days

Tree testing can move fast because the artifact is simple. You need a navigation tree, clear tasks, and participants.

Start by building a text-based tree. This can be your proposed top navigation and key second-level categories. It does not need every page. It needs enough structure to test key tasks and high traffic areas.

Then write tasks that map to real intent, not internal department names. Run a short pilot first. If participants misunderstand a task, rewrite the task before you scale the test.

Finally, analyze results and iterate the tree. Tree testing is designed to be iterative. A few rounds are often more valuable than one perfect test. This is why tree testing is so effective for information architecture for websites decisions that need quick validation. (Nielsen Norman Group)

How to Write Tree Testing Scenarios

A useful scenario is specific but not leading. The pricing is too blunt. You want to understand cost before reaching out is better.

Avoid giving away the label you expect. If your navigation includes Plans, do not write Find plans. Write the intent, not the UI language.

Also include edge cases. If users often search for returns or refunds, include that. If users often search for integration docs, include that. Tree testing is one of the fastest ways to see where findability breaks for real-world needs.

How to Pilot and Fix the Tree Before Launch

Run a pilot with a small group before you run the full tree testing study. The goal is to catch structural issues that are so obvious they distort every task. It also helps you catch task wording problems.

If multiple participants fail a task in the pilot, review two things.

- Is the destination label unclear

- Is the destination in the wrong place

Fix the tree, then run the full test. This approach prevents you from spending time analyzing results that were caused by an avoidable draft structure. It also keeps information architecture for websites work aligned with timelines.

How to Interpret Results Without Overfitting the Navigation

Interpretation is where teams often overreact. A single confusing task does not mean the entire sitemap is wrong. It may mean one label is ambiguous. It may also mean the tree is too deep, forcing users to guess.

Nielsen Norman Group recommends looking at success, first click, and path behavior to understand whether the problem is label clarity or hierarchy. (Nielsen Norman Group)

The goal is to make the tree more predictable, not to optimize for one perfect path. A navigation structure should support multiple mental models, as long as users can recover and still find the right destination.

Success, Directness, and First Click

The success rate tells you whether users reached the right destination. That is the baseline.

Directness tells you whether they got there efficiently. A low success rate is a red flag. A low directness rate is often a signal that the path is not obvious, even if users eventually succeed.

First click is often the most diagnostic. If users consistently click a label that is not the right path, that label is competing with your intended label. That is a naming problem or a grouping problem, and you can usually fix it without rebuilding the whole tree.

Label Problems vs Structure Problems

A label problem looks like this: users go to the right general area but pick the wrong label within it. They are close, but the words are unclear.

A structure problem looks like this: users go to a completely different top-level category, because the grouping does not match their mental model.

Card sorting helps reduce structure problems earlier. Tree testing helps you catch label problems and hierarchy problems before launch. Together, they make information architecture for website decisions more stable.

.webp)

How Card Sorting and Tree Testing Fit Into a Redesign Timeline

Information architecture for websites should be decided before high-fidelity design. If you design first, you tend to protect layouts rather than fix structure. That slows teams down.

A practical sequence is:

- Inventory content and define priority journeys

- Run card sorting to understand grouping and labels

- Draft a sitemap and navigation structure

- Run tree testing to validate findability

- Lock navigation, then design and build

This sequence also improves maintainability. When structure is stable, design systems scale better, and content governance becomes possible.

The Fastest Path From Findings to a Sitemap

You do not need a 50-page research deck. You need a clear output that connects research to decisions.

- A recommended top navigation with 5 to 8 items

- A second-level structure for high-traffic areas

- A label glossary that defines what each label contains

- A list of known exceptions and edge cases

This is where a UI UX design agency approach can be helpful. The goal is not research for its own sake. The goal is decision-grade clarity that a team can build on.

.webp)

Where Teams Lose Time and How to Prevent It

Most teams lose time when feedback splinters. One stakeholder wants marketing language. Another wants product language. A third wants internal department labels. Without evidence, every opinion carries equal weight.

Card sorting and tree testing reduce that stall because they create a shared reference point. You still make decisions, but you make them with constraints. That is often what keeps a redesign moving.

Common Mistakes That Break Findability

Information architecture for websites fails in predictable ways. These are the patterns that show up across industries.

- Too many top-level items, forcing scanning instead of recognition

- Labels that describe internal teams rather than user intent

- Buckets that overlap, like Resources and Insights and Learn

- Deep nesting that hides high-intent pages

- Navigation that changes meaning across sections of the site

One of the fastest fixes is to treat labels as promises. If the label says Pricing, it should lead to pricing or a clear path to it. If the label says Industries, it should lead to industry-specific pages, not a general blog feed.

When information architecture for websites is treated as a marketing asset, labels become part of positioning. They communicate what the business does and who it is for, even before a user reads a single page.

Governance: Keeping Information Architecture Clean After Launch

A good navigation structure can degrade within months if governance is weak. New pages get added wherever there is space. Teams create new categories instead of using existing ones. Labels drift.

Governance does not need to be heavy. It needs to be consistent. A simple approach includes:

- A single owner for navigation changes

- A documented rule for when a new category is allowed

- A quarterly review of top navigation and key second level pages

- A shared naming convention for new pages

This is also where search engine optimization services and IA work intersect in a practical way. Search performance often reflects information architecture for websites because unclear structure leads to unclear internal linking and unclear topic focus. Governance keeps both stable.

If you need an outside perspective without committing to a full redesign, a marketing consultation and audit can be a clean starting point. It helps you identify whether the issue is structure, content, or conversion flow.

.webp)

The Next Step for Teams That Need Clarity

If your site is growing and navigation is starting to feel fragile, do not wait for a full redesign to fix it. A short card sorting study and a focused tree testing round can clarify what users expect and where findability breaks.

Information architecture for websites is not about making a sitemap look tidy. It is about reducing friction in every journey that matters, from discovery to decision.

If you want a second set of eyes on your navigation structure, or you are planning a redesign and want IA locked early, start with the fundamentals and keep the scope tight. When you are ready, start a conversation with Brand Vision about structuring a site that is easier to navigate, easier to maintain, and easier to convert.